Childishly Brutal:

Hunter x Hunter is a shonen manga quite unlike any other. While it does share more than a few similarities with other members of that genre — it’s got a heavy focus on the power of friendship, the character designs are incredibly cartoonish, and most of the fights are built around a distinct power system — it’s possessed of a certain dark undercurrent that you will not find in its kin. Even Death Note, probably the most infamously unorthodox Shonen Jump title in years, doesn’t quite compare to the alarming, often times shocking tone of Hunter x Hunte. Maybe that’s because with Death Note the art style, the premise, and the dialogue all immediately cue you in on the type of story you’ll be dealing with.

Hunter x Hunter provides no such guideposts. From the first page of the first chapter you’re greeted with a sketchy, expressionistic style, wide-eyed and cartoonish character designs, and all the normal talk about “friendship” and “family” and “perseverance.” If you’re the more cautious type, as I was, and not prone to wasting your time picking up yet another voluminous, drawn-out faux-epic on a whim, you might research the series and find that the battles at the heart of the comic are all built around a system known as “nen,” which, on initial reading, seems like a slightly tweaked version of the Stands in JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure (in that the abilities are all highly situational and very tricky, favoring less brute force or speed and more elaborate, long term planning; the overly complex rules that govern this “nen” are like nothing else in any shonen battle series I’ve ever seen). Everything else you’d expect from your stereotypical boys adventure comic — the evil, distinctly named organization made up of various freaks, the obtuse and world-specific terminology, the piles and piles of bizarrely designed and utterly unimportant supporting characters — is there in spades. There is absolutely no reason why an initial glance at the comic, or even a cursory round of research, should catch your interests: the entire set-up screams generic.

But what sounds in theory like the most cliche of cliches is anything but in practice. For all of its talk about “passion” and “spirit” and “the power of guts,” despite a prevailing spirit of romantic, high adventure hanging over everything, Hunter x Hunter is often times so dark that it often feels more a deconstruction of shonen than anything.  As said, there are only inklings of this at first, among these are the casual references to and the curt dismissals of death (“I heard him shouting a while ago, he must have been devoured by some kind of monster,” explains one of the main characters when asked what happened to another examinee. He doesn’t look shocked when reporting this information; for all of his concern he might have been explaining his breakfast plans. His nonchalance is returned in kind.  At another point, the main character, Gon, is presented with the severed head of the man who’d — entirely within the dictates of the rules — stolen his place in the exam. He doesn’t even remark on this) and the utter nonchalance with which characters accept tasks as steep as “dive into this bottomless ravine on a moment’s notice.”

As the exams progress, though, they take an even darker turn: Killua, an eleven year old boy and the other major protagonist in the series, murders a number of participants in a neutral zone for no other reason than that he was frustrated.  There are no consequences for his action; nobody even so much as remarks upon this incident. When he brutally kills another contestant in the examination, nobody’s concerned that an innocent man was ruthlessly murdered for absolutely no reason: they’re concerned only that their friend might be under some mental duress.  By the time the series progresses to its second major story arc, Yoshihiro Togashi (the author) is positioning us to sympathize with genocidal criminals, the mafia, ruthless assassins and maneuvering us to dislike the only character in the series acting on any sort of moral basis. When we hit the Chimera Ant Arc, which in parts nearly abandons the shonen genre in favor of a more horror-themed approach, the series is sometimes unrecognizable: the mood becomes so oppressively morose and gruesome — is there a chapter that doesn’t go by without a named character being eaten and regurgitated in some horrific, twisted new form? — that you either have to accept the result as a brilliant experiment or the author’s descent into madness and depression (a common trope amongst the writers of anime and manga: directors Hideaki Anno and Yoshiyuki Tomino, the creators of Neon Genesis Evangelion and the Mobile Suit Gundam franchise, respectively, are particularly bad about this. There’s a reason 90% of their series end in apocalyptic conflagrations).

What is remarkable about all of this is the author’s lack of judgment in some places and his impossibly judgmental, even self-righteous, tone in others. While some characters, such as Gon and Killua, never meet with recrimination for their murders — in fact they’re even congratulated on them at times! — and there’s never one of those typical, obnoxious moments so prevalent in shonen where the main character is warned that “he can never go back” after his first kill, it’s not uncommon for Togashi to spend pages and pages condemning man’s inhumanity.  One recent chapter showcases random acts of human atrocity (the use of the word “human” is no accident, by the way; he’s comparing the acts of one species to another) — war, genocide, spousal abuse, animal abuse, etc etc — all underscored by some very heavy handed narration. Then, paradoxically, the next chapter reveals to us that a very minor but particularly reprehensible character has gotten off alive and has been rewarded for his monstrous behavior. But this isn’t used to point out any sort of “injustice”: it just…happens. It’s just something to observe, to note, a curiosity that will probably come to nothing in the long run.

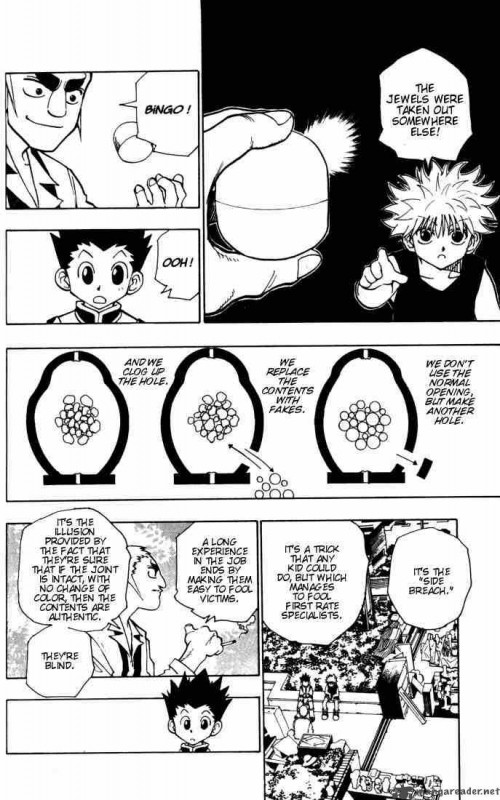

This is not the first of these unresolved cut-aways. The series is, in fact, beset by myriad examples of these bizarre, elaborate, and wordy digressions that have no pay off. The most jarring of these comes in the heart of the York Shin arc. While our main characters SHOULD be tracking down the highly dangerous bounty-heads who will provide them with enough money to buy the item they’re hoping to bid on AND whose capture might propel the plot forward towards something interesting, they leave all of that to their companion. Why? Because they’re too busy talking to a huckster and learning the intricacies of bidding on vases and of the grifts at the heart of the high-stakes, black-market world of antiques That’s right: for absolutely no reason, the plot, which has just resolved the first major beat in the story arc’s climax, takes 4 chapters (that’s roughly half a volume’s worth of material) to explain the intricacies of making and selling a fake vase. While one might hope this interruption is at least elegant or enlightening, it is not: the explanation is hundreds of word’s long and somehow only manages to make an already unclear concept even foggier. The characters — not even the one explaining this to us — are not developed as a result of this interaction, as they’re hardly even present: you may as well be watching a very poorly conceived documentary on the art of ripping off antique stores directed by the world’s wordiest and most boorish pedant. And just in case you were hoping that there might be some pay off from this aside, rest assured there is not. At all. The plan comes to nothing, the side character is dropped, and these vases are never again mentioned. In any context. This plot thread is not so much dangling as it is cut away and left to fall, its frayed remnants a reminder that at some point the story went horribly off-track. A similar event happens in the Chimera Ant arc, where the character Jairo — heretofore undiscussed, unnamed, not even hinted at — is revealed to be of incredible importance. In a panel the focus of the story shifts from Gon’s attempts to refine his nen to a two-chapter explanation of this shadowy overlord and the foreshadowing that he’s going to be a big player in events to come…only to reveal that those events are still YEARS in coming . While this plot thread HAS been picked up once again, its initial intrusion into the story was jarring in the extreme: there were myriad opportunities to introduce it earlier, opportunities that would have been far more fitting in terms of timing, context, and plot, but Togashi passed them up in favor of this far clumsier aside.

These abrupt breaks are not relegated solely to the slower moments in the story, either; Togashi has the absolute worst habit of interrupting the most interesting battles in the series to focus on some decidedly dull confrontations.  Case in point: at the absolute height of a battle royale involving some of the highest level characters in the series — a fight that is the culmination of years build-up, featuring some of the most mind-bending techniques we’ve seen thus far and some excellently implemented character development, all heightened by the ominous presence of an ever ticking timer — Togashi cuts away to show us the game of wits taking place between an octopus and a lobster-man. For a whole stretch of chapters. And the fight revolves almost entirely around opening and closing doors in the proper sequence… It’s enough to kill the mood and the tension that’s been established to this point and is almost enough to make you throw the book through a screen or put your fist through your monitor.

By all rights, this should kill the pacing and thus the tension. Errors and cut-aways as egregious as these should not only be unacceptable, they should be downright damning. But they aren’t. Somehow, Togashi’s warped sense of pacing doesn’t stifle the sense of urgency but enhances it. This meticulous, slow, play-by-play approach to fighting lends itself to far more cerebral battles than those found in other comics which, in turn, increases the tension ten-fold. When the characters are developing as they fight, and when the fights depend on far more than just who can hit harder, faster or whose ability is more versatile, everything becomes a bit more sense. The stakes become greater on both sides because we learn so much about each character as a character based entirely on their approach to combat. Often times, entire battles — entire story arcs– have been decided by a few carefully chosen and brilliantly timed words. Accompanied by some stand-out narration (normally the BANE of action comics),  Hunter x Hunter’s fights take on dimensions that are normally lacking in other shonen: when each and every element of the battle, from the participants’ actions to the madcap abilities they’re throwing around, is indicative of something more than just who’s muscles are bigger than whose, the fights take a tint quite unlike any those in any other shonen. Somehow, Togashi has found a way to use inter-battle flashbacks and captions to poignant effect. Battles that might be rather spare and uninteresting from a purely visual standpoint become captivating as we’re given a play-by-play of every thought that each character is thinking and an examination of the drives behind them. It’s as though you’re watching a match of chess-boxing in which the contestants do not so much alternate between a round of boxing and a round of chess as they play them simultaneously, each move in the chess game having an equal effect on the boxing match and each move providing startling insight into the contestants’ pysche. The end product is fascinating, if sometimes a bit frustrating.

This seems to be the series’ greatest strength: its brilliant ability to frustrate the reader at every turn. In lesser hands — in fact, in any hands but those of a madman — the purposeful alienation and baffling of your readers is a death warrant, and rightly so. Nobody except a masochist takes up a story because they want to be mocked; maybe challenged, but never treated with the contempt shown here! Yet Togashi’s vision works precisely to the extent that it’s insane. No other manga (aside from The World is Yours, which isn’t so much insane as it is garbled nonsense) is quite so manic or so weirdly discordant; yes, there are more violent manga, there are more perverse, and there are more overtly odd stories out there, but none have quite the mad, nihilistic spark that Hunter x Hunter has. None of them have the same “fuck you” punk approach that Hunter x Hunter has, and none of them are as self-indulgent. There’s not, I’d wager, a major, mainstream author out there with weekly deadlines to fulfill who takes quite the glee that Togashi does from ignoring them; there’s no other popular writer out there who’s willing to end 7 years of storytelling NOT with a cataclysmic beatdown but with 9 pages of conversation about chess set against a black background!

Somehow, it all adds up brilliantly. The disjointed narrative style quickly becomes less a frustration and more an engaging curiosity: one cannot help but wonder what bizarre turns the plot is going to take (and one certainly cannot predict!). It’s fascinating to see just how wretched Togashi can draw certain chapters, and there’s not a person out there who will deny that there’s something fascinating in Togashi’s ability to turn the reader’s affections away from the heroes to lie instead with the villains. And in those rare turn-around moments where Togashi DOES decide to move the plot somewhere interesting, or keep a battle on track, or exercise his drawing ability? The results are absolutely LOVELY. Not just lovely, they are often BREATHTAKING. Togashi at his best is, as any fan of Yuu Yuu Hakusho will attest, working on a plane above most manga artists and writers. His dialogue can be as snappy as anyone’s, his choreography almost balletic, his art breathtaking. Any reader who doubts this has simply to read to the climactic fight of Hunter x Hunter‘s most recent story arc, wherein all of these frustrations which have been mounting so steadily are blown apart in a mere four chapters by one of, if not THE, most stunning fights in comic book history.

Like the best of teases, Togashi knows just how to tantalize, knows exactly how to excite and frustrate in a single breath (or, in this case, panel), and knows exactly how to leave his enraged audience begging for more. Mayhaps it’s all intentional; that would certainly go a long way towards explaining many of the anomalies in the man’s life and work. Or maybe it’s just accidental and Togashi happens to be rolling just the right dice every now and then. Whatever the case, it works. There’s a reason that even his editors won’t refuse the man, won’t fire him despite his free-form approach to the business (and it doesn’t have a thing to do with the fact that his wife wrote and drew Sailor Moon or his mysterious, vaguely defined “hand disease): they know that the series wouldn’t work any other way. If they rushed him, if they pushed him to conform to the same editorial standards as anyone else, they’d be killing the series as surely as if they cancelled. They know as well as anybody: you don’t rush a madman, on penalty of your own life.